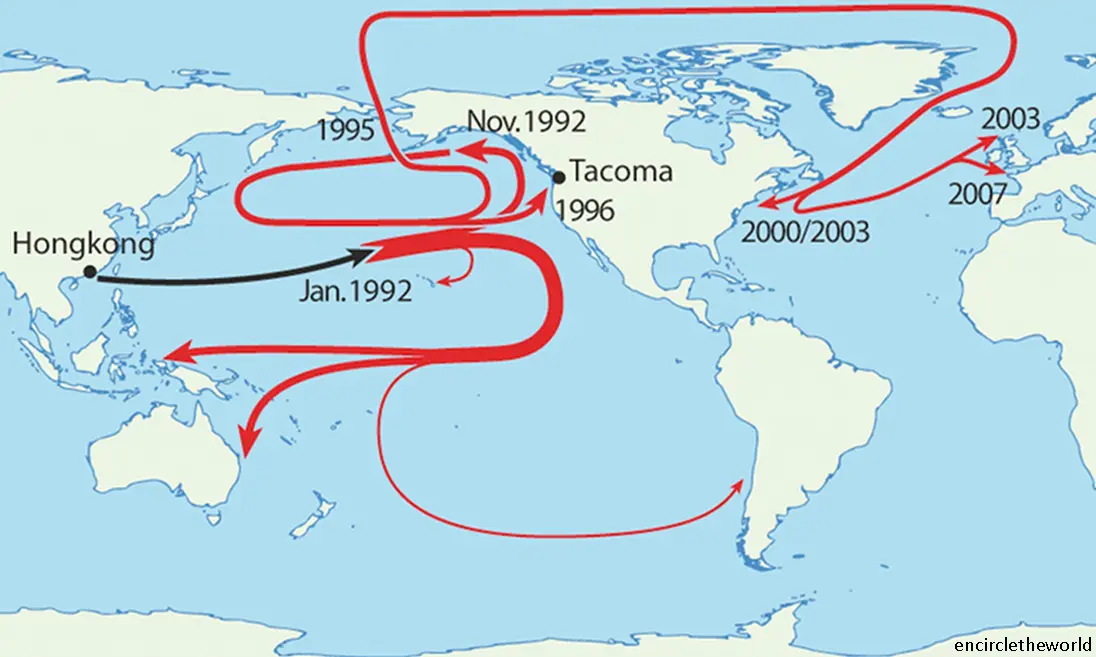

If I were to tell you that rubber ducks have revolutionized how scientists view and understand ocean currents, would you believe me? No? Neither would I, but you should because it’s completely true and one of my favorite science stories! In 1992, a container cargo ship from Hong Kong set out for Washington but encountered a rough storm during the voyage. One of the containers, filled with nearly 30,000 bathtub toys (rubber ducks, frogs, turtles, and beavers) called Friendly Floatees, fell overboard and somehow broke open, releasing all of the toys into the ocean.

These plastic toys, like their name implies, are meant to float in bathtubs as a child’s toy, so once their cardboard enclosure disintegrated they floated to the surface.

Some oceanographers from Seattle, including Curtis Ebbesmeyer, were studying ocean currents and decided to attempt to track the progress of these rubber ducks. They were already tracking another cargo accident – roughly 61,000 Nike shoes that had been lost in 1990! After around 10 months, these rubber ducks started washing up in Alaska, more than 3,000 km away. Using ‘citizen science,’ these scientists contacted many workers and residents on the coast to find out if other toys were appearing. From November 1992 until August 1993, around 400 of these Friendly Floatees were found in Alaska.

Using this information, the scientists were able to input the toys’ voyage into an ocean current simulator. They were able to correctly predict where other rubber ducks would end up! They predicted that many would wash up in Washington three years later, and that many of the ducks would travel between Alaska and Japan, back to Alaska, and then become trapped in the Arctic ice. They predicted that the ice, once in the North Atlantic, would thaw and release the rubber ducks back onto their new paths. Many other rubber ducks were predicted to land in the UK around 2007. Their predictions were indeed correct, aided by a website they set up for anyone to submit pictures of rubber ducks found in the ocean or washed up on the beach, to verify their authenticity. This all might be interesting, yes, but what did it actually teach the scientists?

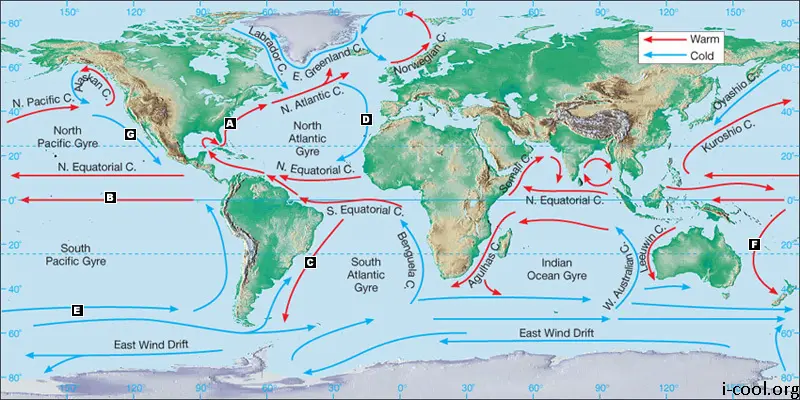

In each ocean there is a main gyre – an area where currents travel in a circular pattern, which happens to be where many of the rubber ducks were and still are trapped. According to Ebbesmeyer, “It was like knowing that a planet is in the solar system but not being able to say how long it takes to orbit.” They found out that some of the toys were able to ‘complete the circuit’ of the North Pacific Gyre and escape in three years. In addition to ocean currents, NASA used the rubber ducks to continue their glacier research.

All of this is important because not all floating debris is as glamorous as an adorable kid’s toy. Plastic and other garbage that float are also caught in these gyres, including an area in the same gyre as these rubber ducks called the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, an ‘island’ of debris that is twice the size of the state of Texas. There are 11 main gyres in the ocean, all of which become home to any plastic or debris that happens to get sucked in by the current. These Friendly Floatees helped raise awareness of this gigantic ‘island’ of garbage while giving scientists valuable knowledge about ocean currents and glacier movement. Rubber ducks may be cute, but used water bottles and plastic bags are not. Remember these gyres that accumulate debris the next time you have the choice between paper or plastic or bringing your own cloth bag to the supermarket!

Your marine biologist /Daniel